Wednesday September 3, 2025

Egypt insists its support for Somalia is not aimed at Ethiopia, but rather at helping a country long plagued by instability and insecurity.

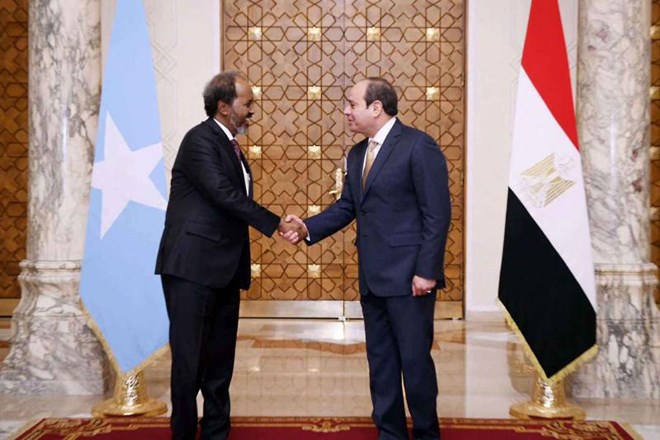

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi meets Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud at Ittihadiya Palace in Cairo, January 21, 2024. (Egyptian presidency)

The announcement of Egyptian troops arriving in Somalia as part of the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) has drawn renewed criticism from Ethiopia, which views the move with great sensitivity, while Cairo insists it is an instrument to safeguard security and stability in a strategically vital country in East Africa, not an attempt to antagonise Addis Ababa.

The Egyptian military delegation included senior officers and special units to prepare for the imminent deployment of Egyptian troops, in coordination with Somalia and the African forces.

Egypt plans to contribute around 5,000 soldiers to the African peacekeeping mission, due to begin in Somalia in January, with another 5,000 assigned to support security at key sites across the country. This follows Mogadishu’s announcement that it would end the mission of 10,000 Ethiopian soldiers stationed on Somali soil.

In September last year, media reports revealed that an Egyptian warship had delivered a fresh consignment of weapons to Somalia, including anti-aircraft guns and artillery.

Every step taken by Egypt in Somalia is perceived by Ethiopia as being directed against it, deepening mistrust between the two sides and preventing progress towards resolving the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) dispute. The planned inauguration of the dam in a major ceremony in Addis Ababa this September threatens to complicate matters further.

Ethiopia’s ambassador in Mogadishu Suleiman Dedefo voiced his country’s displeasure at the presence of Egyptian troops in Somalia, saying Addis Ababa felt neither threatened nor reassured by them and saw “no security benefit.” He stressed that while Ethiopia had no objection to forces from other friendly states, Egyptian troops could pose “a political and strategic challenge” to Ethiopia’s roughly 4,000 soldiers stationed in Somalia.

Cairo has issued no official response to the ambassador’s remarks, but semi-official circles close to the government dismissed them as a repetition of past statements from Addis Ababa aimed at stirring alarm over any Egyptian role in Somalia. These circles accused Ethiopia of deliberately exaggerating events and casting them negatively in order to reinforce suspicions about Cairo’s regional intentions and to dissuade other countries from cooperating with Egypt.

These circles emphasised that Egypt’s activities were transparent, rooted in mutual cooperation, and carried no hidden agendas against Ethiopia. They noted that Egypt has long been one of the world’s most active contributors to peacekeeping missions and enjoys historic ties with Somalia.

Cairo, they argued, is interested in partnership with Mogadishu to counter extremist and terrorist groups such as al-Shabaab, which have exploited Somalia’s instability to entrench themselves in the Horn of Africa.

Dedefo said Egyptian troops “will bring no contribution to stability there … If they are useful, it will be in neighbouring countries such as Palestine, Libya or Sudan,” a sarcastic reference to the array of regional challenges confronting Cairo, downplaying the role its forces might play in Somalia.

His comments came a day after Somalia’s ministry of defence welcomed the deployment of Egyptian forces under ATMIS.

The ministry said Egypt’s participation “reflects Cairo’s growing role in supporting Somalia’s stability and security efforts” and reaffirmed Egypt’s strong commitment to strengthening the Somali National Army through the peacekeeping mission.

The AU Peace and Security Council had already approved Egyptian participation in ATMIS, which completed its first training programme with Egyptian troops in preparation for deployment to support Somalia’s security and stability and to reinforce the army through the mission’s new structure.

In August 2024, Egypt and Somalia signed a military cooperation protocol, agreeing Cairo’s participation in the AU mission from 2025 to 2029. Egypt also delivered military equipment to Mogadishu the following month.

At the time, Ethiopian foreign minister Taye Atske Selassie demanded that the mission should not pose a threat to Ethiopia’s national security: “This is not out of fear, but to avoid igniting new conflicts in the region.”

Egypt insists its support for Somalia is not aimed at Ethiopia, but rather at helping a country long plagued by instability and insecurity through a peacekeeping framework established under a formal military cooperation protocol.

Mogadishu stressed that the decision to include Egyptian troops in peacekeeping operations was a sovereign matter between the two countries, beyond Ethiopia’s say.

Somali Defence Minister Abdulkadir Nur thanked Egypt, declaring that “Somalia has passed the stage where they were dictated to and awaited the affirmation of others on who it will engage with. We know our own interests, and we will choose between our allies and our enemies. Thank you Egypt.”

The row between Egypt and Ethiopia over Somalia escalated after Addis Ababa signed a memorandum of understanding with the self-declared “Republic of Somaliland” in January 2024, granting it access to a seaport, logistical facilities, and a military base.

Mogadishu rejected the deal, with Cairo standing beside it in solidarity. The memorandum was later suspended following Turkish mediation, which produced a principles agreement safeguarding Somali unity while granting Ethiopia port access through arrangements with Mogadishu’s central government.

The agreement remains frozen, however. Turkey was expected to continue its mediation until the deal was implemented, but regional tensions derailed its efforts, leaving Ankara unable to enforce the agreement or preserve a measure of warmth between Mogadishu and Addis Ababa. Both sides are instead manoeuvring to consolidate their positions in anticipation of possible political or military confrontation.

As a result, any Egyptian military presence in Somalia, even under a peacekeeping mandate, is rejected by Ethiopia and seen through the prism of the Nile dam dispute.

Resolving the GERD crisis would provide a path to ending the rift between Cairo and Addis Ababa, but the dam has become a structural issue requiring significant concessions from both sides, concessions that remain distant. For now, Somalia will remain a theatre of ongoing contention.