By Taha Sakr

Monday July 28, 2025

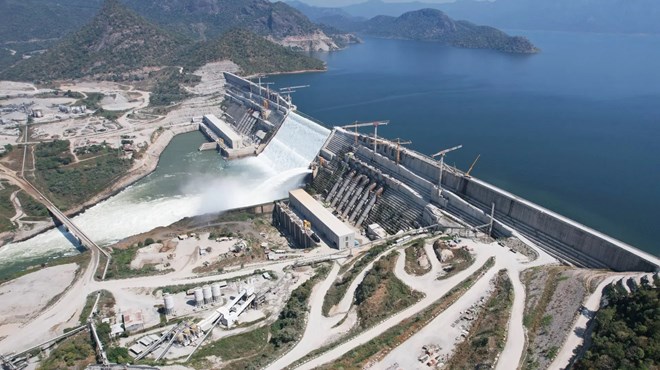

Ethiopia is preparing to formally inaugurate the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) in September 2025, marking the culmination of over a decade of construction on what is set to become Africa’s largest hydropower project. The announcement comes amid persistent regional tensions, as Egypt and Sudan continue to oppose Ethiopia’s unilateral management of the dam on the Blue Nile, a crucial artery of the Nile River system shared by all three countries.

While Addis Ababa hails the GERD as a national triumph and a symbol of economic self-reliance, the project remains a source of diplomatic friction in the Nile Basin. Despite repeated calls by Egypt and Sudan for a legally binding agreement on the dam’s filling and operation, Ethiopia has moved forward with construction and reservoir filling without a trilateral consensus.

Strategic and Symbolic Milestone for Ethiopia

The GERD, located near the Sudanese border in Ethiopia’s Benishangul-Gumuz region, has been a flagship infrastructure project for successive Ethiopian governments. It is expected to generate over 6,000 megawatts of electricity—doubling Ethiopia’s current capacity—and has been promoted as a critical engine for domestic industrialization, rural electrification, and regional power exports to countries such as Sudan, Kenya, and Djibouti.

The upcoming inauguration ceremony, reportedly scheduled to coincide with Ethiopia’s New Year celebrations in September, will showcase the final phase of the dam’s construction. Government officials in Addis Ababa have extended formal invitations to leaders from across the continent, including Egypt and Sudan, in what they describe as a gesture of goodwill and regional inclusion.

The GERD’s financing has been touted as uniquely Ethiopian—funded primarily through domestic bond sales and citizen contributions rather than external loans. For many Ethiopians, the dam has become a unifying national symbol during a period of internal challenges, including ethnic tensions, civil unrest, and economic strain.

Cairo and Khartoum Reaffirm Concerns Over Unilateralism

Egypt and Sudan, both downstream Nile countries, have repeatedly warned against Ethiopia’s unilateral approach to managing the GERD. Cairo, which depends on the Nile for over 95% of its fresh water needs, views the dam as a potentially existential threat to its national water security. Sudan has raised its own concerns, particularly over the risks of uncoordinated water releases that could threaten its dams and urban areas along the Blue Nile.

Since 2011, several rounds of negotiations involving the three countries—mediated at various times by the African Union, the United States, and the European Union—have failed to produce a binding agreement. While Ethiopia has proceeded with successive stages of reservoir filling, Egypt and Sudan have maintained that any operational framework must include clear, enforceable rules on water management, data sharing, and dispute resolution, especially during periods of drought.

In July 2021, the UN Security Council referred the issue back to the African Union for regional mediation, underscoring the lack of international consensus and the complexity of the dispute. However, little tangible progress has been achieved since.

Regional Implications and Geopolitical Dimensions

Beyond its immediate hydrological impact, the GERD dispute reflects broader tensions over transboundary resource governance in Africa. The Nile River, which flows through 11 countries, has historically been governed by colonial-era agreements that granted Egypt and Sudan significant control over the river’s waters. Ethiopia and other upstream countries have long contested the legitimacy of these arrangements, calling for a more equitable allocation of water resources.

Ethiopia argues that the GERD does not seek to harm downstream countries and that its primary purpose is energy generation, not irrigation or water diversion. Nonetheless, Egypt and Sudan continue to express concern that, without a formal and enforceable operating agreement, their economies and populations remain vulnerable to unpredictable water flows and future water scarcity.

In recent years, Egypt has intensified its diplomatic efforts to raise international awareness of the GERD issue, presenting it as a matter of regional stability and water justice. At the same time, Ethiopia has reaffirmed its position that the dam is a sovereign national project and has rejected what it views as attempts to “internationalize” a regional issue.

Dam Completion and Future Water Management

With the construction of the dam structure now largely complete, and the reservoir nearing full capacity, attention is shifting to the operational phase of the GERD. This includes managing the annual inflows of the Blue Nile, which contribute approximately 85% of the Nile’s total volume, and determining how releases will be handled during dry years or extreme weather events.

Water experts have warned that coordinated management is essential not only to prevent disruptions in downstream water availability, but also to ensure that the dam itself operates efficiently and sustainably. In the absence of cooperation, there is a risk that mismanagement or unilateral decision-making could trigger environmental, agricultural, or humanitarian consequences throughout the basin.

While Ethiopia continues to emphasize the GERD’s developmental potential, Cairo and Khartoum are unlikely to soften their stance without concrete commitments on water governance, transparency, and conflict mitigation mechanisms.

Outlook: Diplomacy or Deadlock?

The inauguration of the GERD represents a turning point—not only for Ethiopia’s domestic energy ambitions, but also for the politics of the Nile. Whether this milestone becomes a step toward regional integration or a symbol of entrenched division depends largely on the willingness of all parties to re-engage in constructive dialogue.

Egypt and Sudan have consistently affirmed their readiness to negotiate in good faith, provided the outcome leads to a binding agreement that safeguards their vital water interests. Ethiopia, for its part, insists that any future agreement must preserve its sovereign rights to development.

With no new negotiations currently scheduled, the path forward remains uncertain. For the more than 250 million people who live along the Nile’s banks in Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt, the outcome of this long-running dispute will have far-reaching implications—not only for water security, but for regional peace, cooperation, and sustainable development.